Tools

The profession of straw plaiting required the use of very few tools. The plaiter’s hands were the most important and hardworking tool. A plaiter happy to survive by making whole straw plait didn’t need any additional tools. For those wanting to earn more money moved onto making split straw plaits and needed a straw splitter. Splitters came in various forms, the earliest made from bone, then metal and later the splitters were housed in a wooden frame. Prolific plaiters producing split straw plaits would also have a splint mill either in their house or shared amongst a group of plaiters. This section can only focus on part of the story, more can be found in my book Straw Plaiting.

Straw Splitters

This small tool was an essential piece of equipment for a plaiter. It cuts a whole straw into narrow splints. Straw splitters come in various forms and with varying numbers of cutting fins. The first splitters were most likely introduced into the U.K. for use in the preparation of straw for marquetry rather than the making of straw plait, later being adopted by plaiters.

There is no evidence to pinpoint a date of introduction, references state a period of late 1700s to early 1800s. It seems entirely likely that straw splitters were already being used in Europe where there was an established trade in straw marquetry. This would explain the many references to the straw splitter being introduced by prisoners captured in the Napoleonic Wars and held in the U.K.

A plaiter usually bought their plaiting straws once a week and although the straws were sold in bundles sorted to the same size, the plaiter never knew what the size would be. What the plaiter did know was they had to make the plait to order and it had to be the width requested. Failure to comply would mean a lower sale price, or worse still not being able to sell. Straw plait held in museum collections indicates the width of split straw usually had to be between 1mm and 2mm wide. If the bundle of plaiting straws were thick, the plaiter needed a splitter with a high number of cutting fins to produce this width. If the straws were thin they needed a splitter with a low number of cutting fins. Most professional plaiters would have needed a selection of splitters. The frame splitter which holds a selection of splitters in one piece of equipment must have been a great joy and relief to plaiters.

Horn splitter

This may be the earliest example of a straw splitter and the type used by Napoleonic prisoners. It is rare and unusual to have splitter made of horn rather than bone and although this splitter appears large and cumbersome it splits a whole straw into four sections most efficiently. We do know that the earliest splitters were not attached to a handle but accounts only mention them being made from bone.

Horn splitter: 7cm long, 2.6cm at widest point With four cutting fins Personal collection

Bone splitter

This is a type used in Switzerland in the 1800s. Unlike the horn splitter this has a point which acts as a guide for the straw. This example has twelve cutting fins, a large number but understandable since the Swiss workers used rye straw which has a much larger diameter stem. More cutting fins enabled the wide straw to be cut into splints 1-2mm wide, which were the widths commonly used to make many of the products and plaits.

Bone splitter: 7cm long, 1.5cm at widest point With twelve cutting fins Personal collection

Metal splitters

This type are said to have first been designed and made by a Bedfordshire blacksmith called Janes in the early 1800s. This design saw a change from the earlier splitters with the introduction of a handle. The earliest splitters were made from iron, very few survive. Later types are made from brass or steel, they were made throughout the 1800s. The long point acts as a guide for the straw. Surviving examples range between two and thirteen cutting fins catering for the possibility of splitting a full range of straws from the finest to widest diameter.

Metal splitter: 6.5-7.3cm long Various numbers of cutting fins Originally the guide would have been straight . Personal collection

Detail of metal splitter

Surviving metal splitters are sometimes dug up from the ground, perhaps discarded by a plaiter when it broke, or perhaps lost. Others have been handed down through families and are usually in better condition. By closely examining a splitter you can see that it tells a story of constant use. Look at how the metal has worn away leaving a dip at the junction of the guide and cutting fin. Hundreds of thousands of straws have been split with this tool until eventually the fin broke off rending it useless.

Overall width: 1.8cm, head of splitter: 1.2cm long, guide: 7mm With five cutters Personal collection

Frame splitter

Introduced around 1815 this improvement must have been welcomed by the plaiters. Unfortunately it was more expensive than a single splitter so not accessible to everyone. For the first time all the splitters were in one tool speeding up the splitting process. This type of splitter was made in a range of shapes and contained from two to seven splitters. Each splitter has a different number of cutting fins from three up to nine. The wood used for the frame could be a fruit wood, beech or more expensive mahogany.

Height: 8.3-10.7cm, width: 5.3-5.8cm Personal collection

Detail of frame splitter

This splitter is rare as it is stamped by its maker, Reeve. Reeve may have been an apprentice working with Austin in Akeman Street, Tring who also stamped his name. Splitters stamped by Reeve, Austin and J. Austin were probably not made until the 1830s and later. Everyone assumes Austin and J Austin were the same person but we simply do not know. Austin was a common name around Tring and there were other wood workers called Austin. Splitters stamped with names are highly prized since the majority of examples are unsigned but it is important to realise there were makers other than these two. These can be found in the collection at Wardown House Museum, Luton.

Reproduction tube splitter

This is a modern copy inspired by a tube splitter in the collection at Wardown House Museum, Luton. It was made by Gordon Thwaites of Cumbria in the 1990s. The original was used in Belgium, where there was a significant plaiting industry in the 1800s. The cutting fins are housed within the brass tube. As with other types of splitter there is a metal guide. Both originally and with the reproductions, tube splitters were supplied with various numbers of cutting fins.

Overall length: 3cm, width: 1.2cm . With six cutting fins Personal collection

Reproduction stem splitter

This is another splitter made by Gordon Thwaites in the 1990s. Originally, in the 1800s, some metal splitters were finished with wooden handles of different shapes. Addition of a shaped handle does make the splitter easier to grip. This handle is made from yew whilst examples from the 1800s are usually made from fruit woods or beech; whatever wood was available to the maker.

Overall length: 10cm With five cutting fins Personal collection

Reproduction frame splitter

Gordon Thwaites also produced a frame splitter housing splitters with four to eight cutting fins. He based the shape on an Austin splitter in the collection at Wardown House Museum in Luton. Like Austin he stamped his name but also numbered each splitter. Bearing the number 1, this is the first one made in the 1990s. All Thwaites splitters were precision engineered from brass. To ensure long wear the guides are made from steel.

Length: 9.3cm, width: 5.1cm Five splitters, with four, five, six, seven and eight cutting fins respectively Personal collection

Modern splitter

Made from plastic this splitter with six cutting fins harkens back to the earliest shape of splitters. It is available from suppliers in Switzerland and although it perhaps doesn’t have the aesthetic charm of the original splitters it is a highly effective tool. Straw workers who use this for their decorative work often call it a torpedo splitter.

Length: 8cm, width: 6mm With six cutting fins Personal collection

Modern splitter

These donut shaped splitters are used today when making straw stars. They are available from Germany with suppliers selling on various sites. They are made with two, three, four or six cutting fins.

Diameter: 4.9cm, height 1.8cm With two and three or four, six cutting fins Personal collection

Palm and straw splitter

This type of splitter was used during the late 1700s and 1800s in the American straw plaiting industry which was based along the eastern seaboard of the United States. Although sometimes marketed as a straw splitter it was more effective for splitting the flat leaf of a palm. The palm, or a straw that has been split open into a flat tape, is pressed onto the cutting blades, the metal bar is pressed down and the palm pulled through. The splitter was available with various numbers of cutting blades so a variety of widths could be split. This example has eight blades and would produce a splint 1.5mm wide.

Length: 10cm, width: 1.4cm, overall width of cutting blades 2cm With eight cutting blades Personal collection

Straw mills

It is not clear when mills were introduced but reference to them is found in workhouse records dated 1771. They are generally made from beech wood, for the frame and boxwood for the rollers.

There are two types of plait mill one for softening the split straw (splints) and another for milling or flattening the plait. The mill was fixed to a door jam or wall in the plaiter’s home. Splint mills were a relatively expensive tool to purchase so were often shared between families. Plait mills with their grooved rollers were only used in factories or homes of professional hat makers. In Essex plaiters used rolling pins to both soften the splints and flatten or straighten the plait.

Interestingly different forms of mills are found in both Switzerland and the USA, the mill being fixed to a long bench on which the operator can sit.

Splint mill

This mill has two smooth rollers. By turning the screw the gap between them decreases and increases pressure on the straw splints as they pass through. The purpose of milling is to soften the straw not to flatten it. Inside a straw stem there is a layer of soft pith, by compression the straw becomes more pliable and easy to work. Some plaiters probably also used a splint mill to flatten and straighten finished lengths of plait.

Height: 47cm, width: 27.5cm, frame depth: 6.2cm, diameter of each roller: 8cm Probably made in the mid 1800s. No maker’s mark. Personal collection

Plait mill

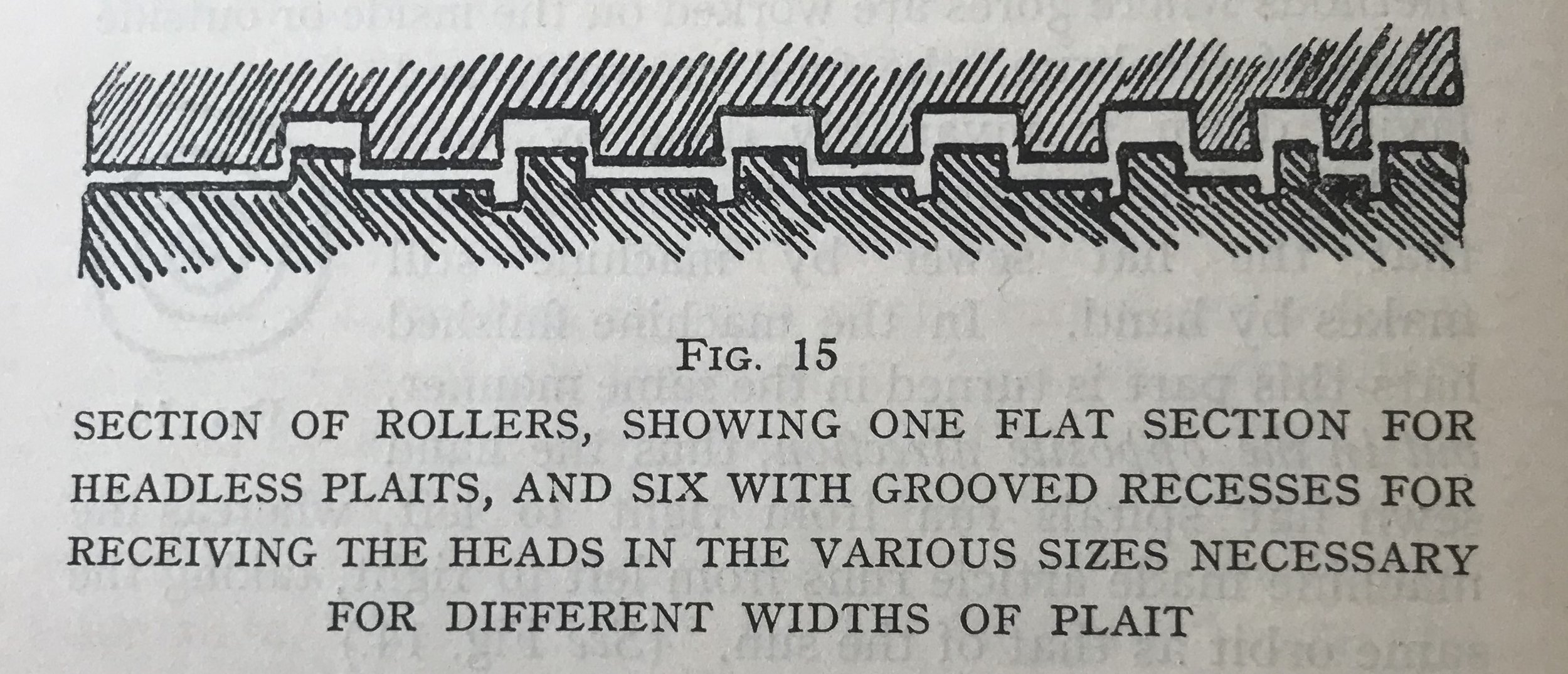

Unlike splint mills, plait mills usually have grooves of various widths along the rollers. These grooves fit into each other so the plait passes through the groove and is pressed by the corresponding protrusion on the top roller. Originally these mills were made from wood but later from metal since the tougher straw of imported Chinese plait, and the constant use. The grooves caused the plait to both flatten and straighten.

Image courtesy of: Tring Local History Museum, Tring, Hertfordshire

Various accounts tell us that plait mills were used both for flat plaits and for those with a decorative edge. In his book Harry Inwards explains how this was achieved. When looking at an actual mill this feature is extremely difficult to see therefor his diagram and explanation is most useful.

Extract from: Straw Hats, Harry Inwards. Pitman, 1922, page 82.